Overnights are... boring.

The other night, I handled my first working fire, and a simultaneous medical transport across town, and it reminded me of just how good it could be. Since then I've been acutely aware of just how bored I am. As I told one of the officers who asked me how the "night life" is treating me: I'm too much of a junkie for overnights.

While searching for something to do to pass the time, I came across this game.

There are a lot of things about my job that could be game-ified, and the fact that I work from a screen and mostly interact with emergencies through a digital map and a telephone means it will likely translate well to the video game format.

Of course, it's important for a person working a high-stress job to have a life away from work. Participating in leisure activities that have nothing to do with work is crucial to maintaining balance. Buying this game is probably the last thing that a healthy, well-adjusted dispatcher ought to be doing.

So, naturally, I bought it.

What can I say? I'm a junkie.

Before taking the plunge, I took a look at some reviews.

"I only recommend this for people who get a kick out of sitting behind a desk and not doing alot," reports Steam user Corbwashington. "Wasn't for me." Well, I appreciate the honesty, at least.

According to his profile, Corbwashington, also known as Matt from Australia, has left reviews on 84 other games. With a whopping 1,100 games owned, I imagine "not doing alot" is kind of Matt's forte. But I have to admit, he definitely nailed what it can sometimes feel like to work overnights.

More optimistically, PANZER expresses their wishes that, "every urgency operator would have played this game and scored high before taking a job as an operator in real life," because "It really teaches you what to do in urgency situations."

As an Urgency Operator myself, I guess if I don't score well, it'll mean I don't have the chops to handle "urgency situations" and should probably quit now. (Actually, there is a test, called the CritiCall, that dispatchers have to score well on before being considered for the job, so maybe PANZER is onto something...)

Well, let's see how I do.

Game on.

1. Tutorial

In lieu of a generic loading screen, I was instead treated to a handy little information guide. There were about 26 cards, each with some real-world information or advice. There were tips for interacting with 9-1-1, brief but surprisingly accurate first aid infographics, and this summary of the role of a dispatcher:

I wouldn't feel right about disseminating this provided information without also clarifying some points.

First of all, there's no such thing as an "ignorable" call. I can't speak for every PSAP, but both I've worked for had a no-ignore policy. Every call, no matter what, gets dispatched. After 30 seconds, any call still unanswered automatically reroutes to a backup PSAP, which can then decide to transfer it back to us, dispatch their own units as mutual aid, or take down the information and advise us later. Responding units may decide that a call doesn't require response-- but that rarely happens. And even then, calls are always processed and logged.

Second: while I haven't worked in every PSAP in the world, there surely is room to argue about the statistics. For one thing, I could not find anything to back up the claim that we take 150 calls a day. At my first job, I worked at a center that dispatched for six small-ish towns, with a combined population of about 50,000. On a busy day there, the primary call-taker might take upwards of 20 calls, often clustered around major incidents with multiple reporting parties. But my typical count ranged closer to about 10.

Now, working for a small town of less than 10,000, things have slowed down considerably. Days might see between zero and 5 calls to 9-1-1, but the business line rings right off the hook. Eves are busier for emergencies but slower for the business line, and night shifts, which I now work-- well, let's just say I usually have plenty of time to play silly games like this one.

Also, in my experience, I'd estimate that maybe a quarter to a fifth of the calls I'd take were "empty."

By "empty," there are a few different things I'm assuming they mean, and we have a term and SOP for each: - A hang-up that comes in too quickly to even pick up is called an "abandoned" call. We follow up with those by calling back if the phone system was able to collect a call-back number.

- If we're able to pick up a call but there's no verbal contact made, that's called an "open line," for which we initiate silent call procedure.

- True "prank" calls are rare, and I've personally never taken one. I know people who have handled "SWATTING" incidents and things of the like, but even those are pretty few and far between.

Prank calls, in fact, are criminal offenses-- but the bar for which we deem a call a "prank" is pretty high.

Most calls made to 9-1-1 are reporting emergencies, but sometimes, they're just well-meaning citizens reporting things that might become emergencies, such as a low-hanging telephone wire, or a friend or family member who has been out of contact for a concerning amount of time. Other times, they're accidents.

Accidental calls are pretty common, and make up a large percentage of the calls the game-makers would probably describe as "ignorable." If you call 9-1-1 by mistake, don't panic. Don't hang up, and don't lock yourself in a bunker expecting cops to jump through your windows to arrest you.

The best thing you can do is just stay on the line, confirm with the call-taker that it was an accident and that you do not need emergency services, and answer any questions they ask. Answering them helps us because we have to keep careful records of any calls made to 9-1-1.

However, the fact that these slides exist at all is a testament to the game designers' seemingly genuine desire to treat emergency dispatch work with respect, so they get points for effort with that one.

The first thing I do when I come in for a shift is adjust the room to my preferences. Turn down the lights in the dispatch office, set the thermostat, make a cup of coffee, throw my dinner in the fridge, and stash my coat and backpack in the corner.

Next I settle at the computer and launch and sign into a boatload of programs:

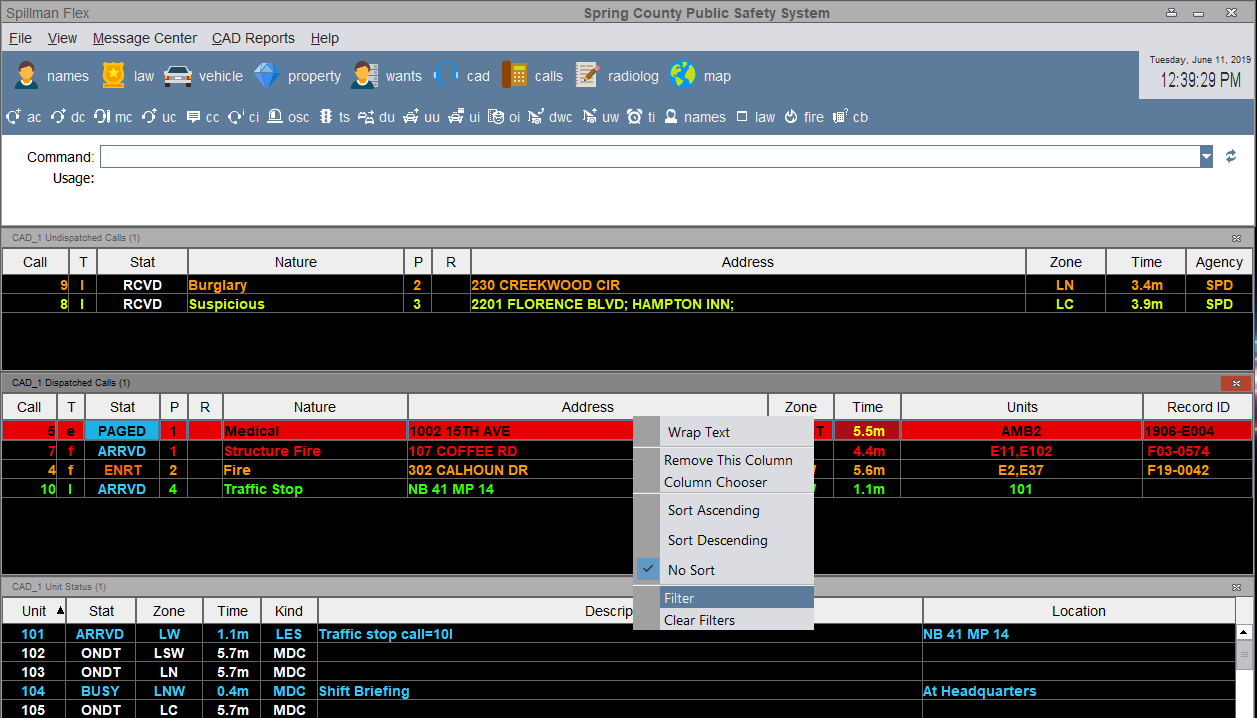

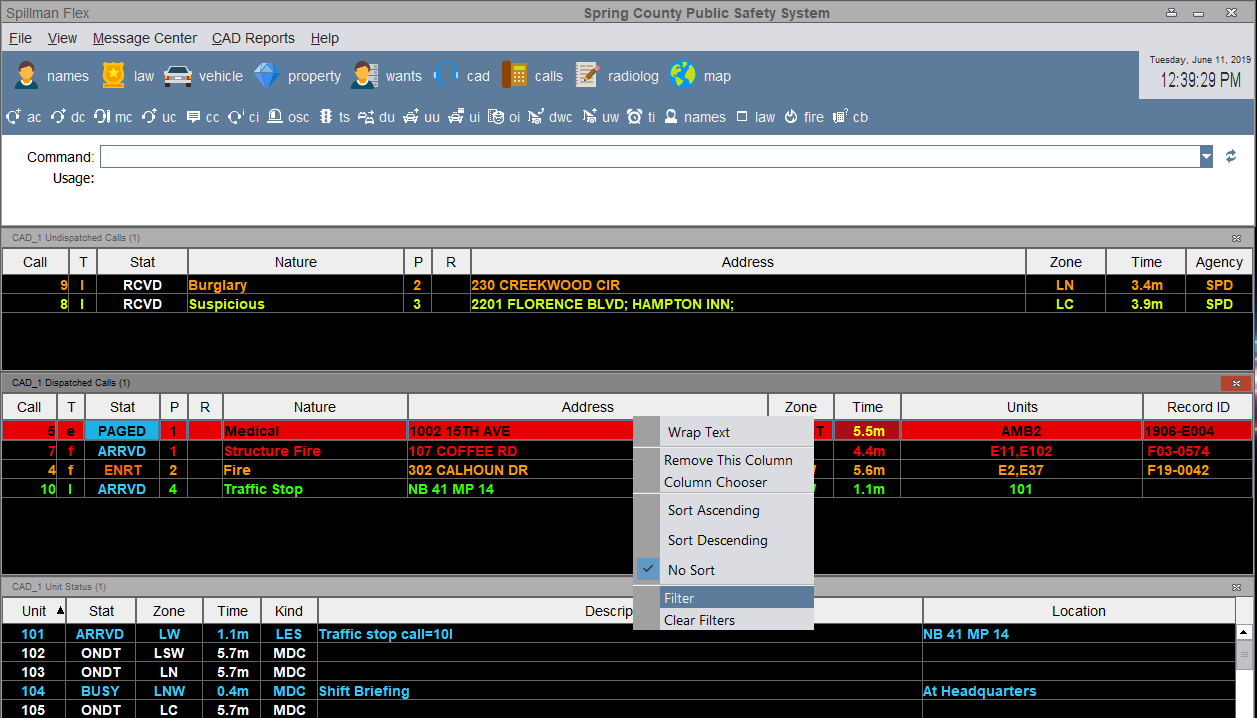

- CAD: Computer-Aided Dispatch software. This is the main platform on which I spend most of my day, assigning my units to calls and logging timestamps. The CAD program also stores previous calls, so I can access and cross-reference as necessary, and so the officers can use official logs when writing their reports

|

Example of what a CAD screen might look like, with information such as who's responding to what

calls, addresses and call natures, and each units' status: available, en route, arrived, or out of service. |

- The 9-1-1 phone system and its associated mapping system

- RapidSOS: a web-based service with more accurate mapping than the 9-1-1 phones have, as well as other available information that's associated with a phone number

- CJIS: a couple of different programs we use to access Criminal Justice Information Services

- Another mapping program with the town's fire response assets (hydrants, sprinklers) and liabilities (gas lines, HAZMAT concerns), along with building information relevant to a fire situation

The game, however, opens with the player actually making decisions that would, in reality, be way over their pay grade. You start out with a budget and a list of officers, vehicles, and equipment, and have to build your response units from scratch.

Choose what sort of police vehicle you want, staff it with officers, and buy them all weapons, bulletproof vests, and first-aid kits. How much you spend depends on how many and which resources you purchase for each unit, but I'm guessing that the cops with cheaper guns will likely cost me in the long run.

Forgetting for a moment that every decision made on this page is one made by people who make two to ten times what I do, I think it's an interesting look into how emergency response is staffed.

Part 3: Dispatching

Once you've stocked your units and set them loose on the town map, you're then brought to the screen from which you will be interacting with your responders. It's comprised mostly of a large map of your jurisdiction, with little icons scattered across it to represent your responders' locations.

When calls come in, a little icon will appear at the address of the call, color-coded by type of situation reported there. To dispatch a unit to a scene, you click on the units you want to respond, then on the dot on the map at your location. A line will appear between the two and a timer will tell you how long until the unit arrives.

I can't speak for other PSAPs, but neither of the ones I've worked for have used tracking on our responders. My town is split into two hemispheres, and patrol units (usually a single officer in a cruiser) are free to meander around the sector assigned to them that day, looking for trouble or speeding cars. Occasionally, my officers will self-dispatch "general patrols" in the CAD, which keeps me posted as to their approximate locations, but they don't do this nearly often enough for me to have their real-time location at any given moment.

Unlike in the game, I also don't dispatch with buttons on a map. In reality, what I do is relay the address and a summary of the situation over the radio.

Also, it's a general misconception that it's always up to the dispatchers who to send to a call. While there are certainly times when I have to use my judgement to decide if a call requires a police, fire, or EMS response (for example, if a child was reported missing in the woods: I'd send an ambulance as well as police, but Kara says that unless she had reason to believe the child injured, she'd hold off on EMS until instructed), most towns have determined procedures. If SOP dictates that police respond to vehicle lockouts and fire responds to residentials, then it doesn't matter what I think. I'll send police to the vehicle and the fire department to the house.

Most of the gameplay is made up of directing responders to calls in this way. Some come in as 9-1-1 calls that you have to simultaneously manage, while others just pop up as notifications. As the dispatcher, you decide which ones take priority, and send the appropriate units using the map.

In reality, all of my dispatching happens over the radio. I put the calls into the CAD as soon as I have the chance to, and once my officers let me know that they're responding to a call, I mark them as 'responding.' When they tell me over the radio that they're on scene, I mark them as 'arrived.' Same when they're clear, and for Fire/EMS units, same when they're en route to the hospital, leaving the hospital, and back in the station. That stuff doesn't happen automatically: I put it into the system as they tell me their status.

Part 4: Call-Taking (Police)

At random intervals during the game, a 9-1-1 call will come in as a tiny little headset notification. If not clicked fast enough, it times out, resulting in a missed call.

If you do manage to click it in time, a little window pops up, with a transcript of the conversation followed by a series of options as to what you, the call-taker, can say. There is also a button at the bottom to "IGNORE."

My first call went like this:

Operator: "9-1-1, what's your emergency?"

Caller: "Hello, there is a fight out on the street! Please, send the police quickly!"

The given options were: (1) how many people, (2) whether there were any weapons, and (3) if anyone was injured. None of these would have been my first question, but let's roll with it, and I'll dissect it more in depth later.

Operator: "Can you see if they have any weapons?"

Caller: "One of them picked up some kind of club!"

Operator: "Could you give me a precise address of the incident?"

Caller: "Yes, of course. It's at 255 East Spring Street."

Finally, we're getting somewhere. With the address given, a new icon populates on my map, and I can send my nearest units, two cars with two officers each.

Except... there is one little problem. In the game, I can't start help until I hang up with my caller.

Operator: "I'm sending emergency services right now."

Caller: "Thank you. Bye."

Well, that could have gone better. Let's roll that again, and this time, we do things my way.

Me: "9-1-1, this line is recorded, where is your emergency?"

Not all places require that you indicate that 9-1-1 calls are recorded, but they always are. As a precaution, then, the PSAPs I've worked for make sure to include it right there in the greeting.

As for the second part, it's simple. It was something Reg asked me in my interview: "If you are only able to get one piece of information from a caller, what do you want it to be?"

Location, location, location.

I might sound like a desperate real estate agent here, but it's the truth.

If I know what you need, but not where you are, there's not much I can do to help you. Your dad is having a heart attack? Sorry, I can't send you an ambulance, because I don't know where the hell I'm sending it. I mean, I can EMD it, try to give you CPR instructions over the phone-- but unless you're a doctor (and if you are, you don't really need me to EMD it, anyway) you're not going to save him.

However, if I know where you are, even if I don't know what you need, I can still send everyone. Once they're on scene, they can duke it out amongst themselves who stays and who cancels. The important thing is to know where.

So that brings us back to the call.

Me: "Just to confirm, you're at 255 East Spring Street?"

Repeating back to them the address makes sure I heard them correctly. It gives them the chance to clarify that either, yes, that is where they are right now, or no, they're somewhere else, but the emergency is taking place at that address. It also helps to help establish a rhythm for the call: I ask, you answer, rinse and repeat. It is important that I maintain control over the call, allowing for my training to supersede her panic, which may threaten to derail the conversation.

Caller: "Yes, that is correct."

Me: "Okay, ma'am, tell me exactly what is happening."

Caller: "There is a fight out on the street! Please, send the police quickly!"

Me: "Okay ma'am, I'm getting help started now. Please stay on the line while I get the police going."

This is the point where I'd dispatch my officers, saying over the radio something like:

"Control to all available units, we have a 9-1-1 caller reporting a physical altercation in the area of 255 East Spring Street. Gathering more information now."

My next focus is safety, for my caller and for my responders.

Me: "You said there's a fight; are you involved in the fight? No? Okay, good. I want you to stay a safe distance away from them."

Caller safety established: check. On to scene safety. My officers' first priority will be to secure any weapons, so my first priority is identifying what, where, and how many weapons they'll be looking for.

In this case, when Andrea tells me that one of them has a club, I'll want to follow up on that, get a description of the person wielding it, and instruct the caller to keep me informed of his movements.

Some other things I might ask from here:

- "How many people are involved?" -- This will help decide how much manpower is needed to subdue the incident.

- "Is there a safe place nearby you could go to and wait for the police to arrive?" -- Because... duh.

- "What is your name?" -- Knowing her name will help me establish a connection with her. She'll be more cooperative, and if I need to snap her out of a panic, her name is a good way to get her attention. (For the sake of talking about this call, let's say her name is Andrea.)

By now, in my town at least, responders will usually be on scene. But in a bigger town, or in cases where storms or accidents delay responders, there may be a longer response time. In the meantime, I want descriptions. I want to know if Andrea knows the involved parties, and if possible, can she give me enough on them to run them out. I want to know if Andrea witnessed how the fight started, heard anyone making threats, or saw anything before things escalated.

If I have to disconnect before they get on scene, I'll end the call with:

"If anything changes before help arrives or if you need any other assistance, call us back immediately at 9-1-1."

Part 5: Call-Taking (EMD: Emergency Medical Dispatch)

While most of the calls that came in on the game were police-oriented, there were a few fire and EMS calls too. I won't go into as much detail with these, but as with the call about the guys fighting in the street, location should have always been first.

Instead, I often got questions like, "Is it possible that he's drunk?" in response to an unconscious male.

I don't care if the unconscious male is drunk. I don't even care that he's unconscious-- yet. I can worry about that once I know where I'm sending the ambulance.

The second thing I need to know with a medical call is what's going on. Tell me the reason you need an ambulance.

Third thing I need to know: is the patient conscious, and are they breathing? A negative to either of these starts a "hot response," and I now have to start CPR instructions.

The calls that I took in the game didn't always have the best options given, and if I were to handle real-life medicals the way I had to handle them here, I'd be out of a job tomorrow.

Something that I did like, however, was the callers' sensitivity to my timing in choosing a reply. If I didn't reply quickly, they started to panic, and would ask me, "Hello, are you still there?"

This was probably the most realistic part of the entire game for me. Just like in real life, these fictional callers were panicky and prone to impatience.

As far as call-taking is concerned, I have to say I'm disappointed. In real life, the questions I ask, how effectively I can collect and relay information, and the way that I process 9-1-1 calls can have the potential to save or lose lives.

Location is first, because without it, nothing else matters.

Second is scene safety. If I don't clarify to EMS that the puncture wound they're responding to is a stab wound, advise them to stage outside until the police clear the scene-- well, let's just say that I don't want to be the reason my EMTs get stabbed.

Third priority for medicals is the patient's "A/C/B" status: Alert, Conscious, Breathing. I need to know if the guy passed out in the sidewalk is breathing before I need to know if he's drunk. The difference between EMS response for a drunk unconscious male and a sober unconscious male is zero. It's the same response. But if I tell them he's not breathing? That turns up the heat immediately.

My point is, I wish the game rewarded effective call-taking, beyond timing how long you take to select a dialogue option.

Conclusion

I really hope that PANZER's implication, that success in this game was in any way indicative of success in the real thing, was misguided, because--

|

| At least the game has one thing in common with my first dispatch job. |

In some ways, this game was reasonably successful in conveying an impression of emergency dispatch. I still wouldn't call it accurate to life.

Many of the gameplay mechanics rely on the player managing things that dispatchers would not have control over in real life. The most egregiously inaccurate functions include:

- Funding and stocking the police and fire departments

- Directly managing the responses of units on your map

- Calls "timing out" and being marked as unanswered

- Not being able to dispatch a call until after you disconnect with the caller. (If it had been possible to do this while call-taking, callers' time-sensitivity would have been more meaningful, as you would be racing to start help while trying to also managing the call-- just like in real life.

- The right questions not always being offered in dialogue choices

- Encouraging players to gather information from 9-1-1 callers that would be irrelevant in real life

In all fairness, many of these choices-- especially the first and second points-- were made in order to make dispatch more hands-on, for the sake of gameplay. But had they been executed more effectively, I think there was potential. For example, the call-taking procedure could have been refined, directly rewarding players for gathering useful information.

For all that was wrong with the game, though, I appreciated a lot too, including:

- The ambiance, which reminded me of Reg's radio room

- Callers being sensitive to time, putting pressure on you to make quick decisions

- Having to manage multiple things at the same time, which is a real-life skill that dispatchers must develop

- Allocating resources properly so that the most critical situations were dealt with first

- Being rated on how quickly your teams responded to calls

- Missed calls being counted against you (because even though no 9-1-1 call is allowed to go unanswered, having them constantly bounce will count against your PSAP)

All in all, not a terrible way to pass a dull shift, but definitely not worth much more than I paid for it. Would I recommend it as a training resource for future dispatchers? Certainly not. At best, the game makes for an entertaining perspective on my job from what is clearly an outsider's point of view.