Discussion of topics such as sexual violence and trauma. Discretion advised.

The phenomenon of being particularly perturbed by a specific auditory stimulus, be it someone chewing with their mouth open or the squelch of bubble wrap pulled taut, is referred to as misophonia. The etymology can be traced to the suffix -phon, referring to sound, and the prefix miso-, meaning "hate." These are the sounds that you especially hate, like the proverbial nail/chalkboard affair.

In fields saturated with tragedy, such as public safety, law enforcement, or intervention services, we all have misoforms-- even dispatchers, who take disturbing calls for a living.

For many, anything involving a vulnerable population can be particularly disturbing, with many dispatchers finding calls from or about children, the elderly, or members of the disabled community to be their personal misoforms. Some are bothered more by the scope of an event than the demographics involved, such as mass casualty incidents, while still others may be sensitive to brutal injuries, harm to animals, or sudden loss of life.

My own personal misoform, likely a result of both first- and second-hand experience, is also a common one: nothing stays with me quite like stories of sexual violence.

Amidst the current cultural revolution of the twenty-first century, there’s no paucity of narratives on the issue. Countless essays, articles, and news stories present the information again and again, while slam poems by students fed up with being reduced to a grim statistic and testimonies aiming to biopsy rape culture all flood the expositional marketplace.

In short, there’s not much use in yet another blog post rehashing how shockingly pervasive sexual violence is or driving home how pernicious the effects of it are. Instead, what I’d like to offer is the story of my first professional exposure to sexual violence, and explore the strange (and often counterintuitive) ways in which we process our misoforms in the professional field.

About a year ago, when I was first considering whether or not to seriously pursue this career, I wanted to be sure that I was going to be able to handle the harder aspects of the job. So, I started watching and listening to things like 9-1-1 call recordings, criminal interrogations, and body cam footage from disaster scenes, trying especially to place myself in the shoes of the call-taker processing a difficult call. By the time I felt sure about going forward in the application process, I had already come across many accounts of sexual violence, and none of them had me reevaluating whether I really wanted to leave my old job.

About a year ago, when I was first considering whether or not to seriously pursue this career, I wanted to be sure that I was going to be able to handle the harder aspects of the job. So, I started watching and listening to things like 9-1-1 call recordings, criminal interrogations, and body cam footage from disaster scenes, trying especially to place myself in the shoes of the call-taker processing a difficult call. By the time I felt sure about going forward in the application process, I had already come across many accounts of sexual violence, and none of them had me reevaluating whether I really wanted to leave my old job. But I knew it would be a different story once I had taken a call for it myself, which brings this story up to the present.

The 9-1-1 call came in at shift change. I grabbed instinctively for the phone, despite the fact that Dave was pretty much set up to take over operation by then. Tired, wired, and mentally half clocked out as I already was, I should’ve let him.

The caller explained to me that she and her husband have been having issues, and that lately they haven’t been getting along at all. Today, she said, he had exposed himself to her, demanding that she help him get off.

For a moment I deliberated between dispatching this as a verbal altercation, or a sexual assault. Even though the latter was, by definition, accurate, sending my officers into the situation with the words, “sexual assault in progress” was priming them to go in guns blazing, potentially escalating something that needn’t otherwise get physical. I needed more information, but the caller had already hung up.

Well, a little voice inside me said. Is that really so bad? It clearly isn’t a real sexual assault, is it?

This sudden, captious thought, nearly unrecognizable in its acrimony as my own, brought me up short. I tried to shut it down, but the internal voice insisted: That’s not what real victims sound like and you know it. She’s using 9-1-1 as a scare tactic to win a fight. Her husband may be a pig, but she’s--

I bit down suddenly on the inside of my cheek, so hard it drew blood. The sharp pain cleared my head, silencing that awful internal voice I didn’t want to believe could be my own.

Cognitively, I knew that what it said was untrue, or at the very least, irrelevant. From a dispatch perspective, it doesn’t matter whether he actually intended to assault her or not. The only thing that mattered was that she felt the situation warranted emergency response, and it was my job to make sure she got just that.

But emotionally, something else was happening inside me, and I wasn’t exactly in a place to address it.

When the officers arrived on scene, Dave was able to take over, and he shooed me away from the dispatch desk. My hands were still shaking as I packed up to leave. On my way out, I slipped into the bathroom, desperate for a moment of peace in which to collect myself.

For years, I've parroted that marital rape is still rape, that there's no excuse for sexual harassment, and that we all need to believe victims. In all of my pre-employment research, I’d listened to calls reporting sexual assaults of all kinds, and every time I had felt the same thing towards the callers: compassion. I always thought that the same compassion would be my first instinct if (or rather when) I eventually took a call like this, empathizing with anyone who’s experienced the same kind of violence as I have.

But as soon as I was faced with a caller who didn’t sound exactly like I thought she should, as soon as I was faced with an “imperfect victim,” I was suddenly spouting all sorts of virulent rhetoric. Where had this sudden onset of victim blaming and judgment come from? It was as if there was a little pick-me hiding beneath the façade: pick me! I’m not like other victims! I did everything right, so what happened to me couldn’t have been my fault-- not like this victim, who was clearly--

Clearly... what? "Asking for it?" Somehow more "deserving of it" than me?

|

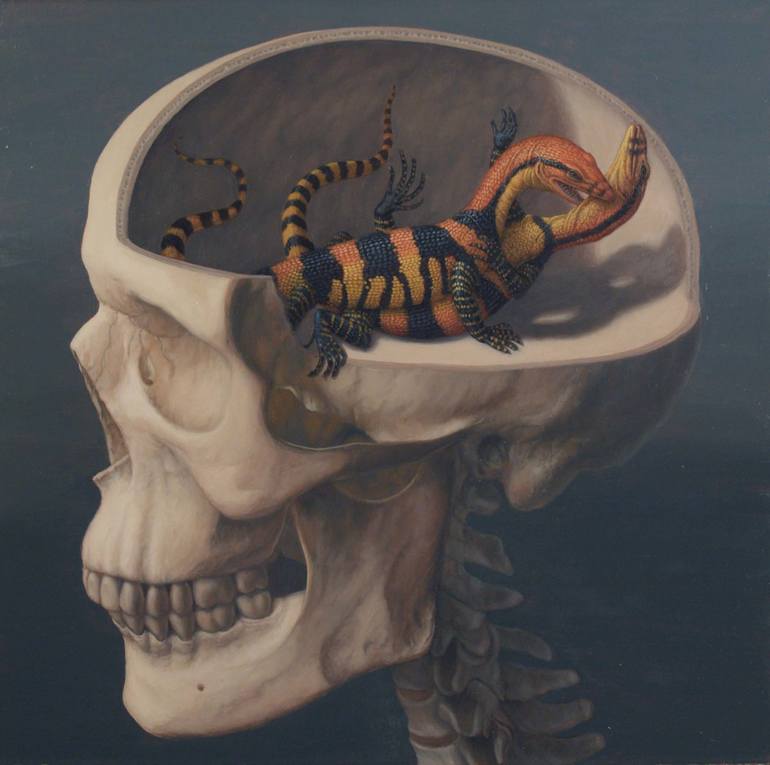

| Sandra Yagi: "The Lizard Part of my Brain #2" |

That morning, I went to sleep feeling irredeemable, but a full night of sleep helped me gain a bit of distance. Talking through the experience with Gabe and Kara gave me a sense of peace, as I gave a name to the nameless, nebulous darkness clouding my thoughts. Writing up an email to Kenneth about how I might’ve better handled dispatching the call helped me understand how it had affected me, and hopefully allowed for some professional growth, too.

In the end, I came to the conclusion that taking this call had dredged up something in me from a long time ago, a helplessness that I had thought myself past. Listening to her made me remember the isolation, hopelessness, and despair I’d once left behind, and instead of seeing that resurgence as a reason to sympathize with her, I had automatically associated it with-- and therefore projected it onto-- her.

"This call is upsetting me" became “It’s her fault I feel this way,” which in turn became “it’s her fault this is happening at all": a lie from which nobody walks away unscathed. Hating this woman was nothing more than a misplaced attempt to regain control over the uncontrollable, to further distance myself from my past.

|

| "Her fault. Her fault." The Handmaid's Tale, 2017. |

Kara reminded me that the first response you have to something is your conditioned response, whether that be from a pervasive social narrative or the survival instincts of a traumatized psyche. It's your second response, the one you intentionally choose and act upon, that reveals your values and beliefs. Intrusive thoughts may often be a result of trying to deflect from a sore spot, some abscess that resists being drained, for so long as it has been hidden out of sight.

Sexual violence is my misoform, and no amount of dispatch training is going to prepare me 100% for everything I might deal with. This wouldn't make it okay for me to start engaging with rape culture propaganda, but it does explain where that odious little voice came from. It would never make it okay to mishandle or ignore anybody's call for help, but understanding how complex PTSD wreaks havoc on the mind can lend legitimacy to my fight against my own internalized issues, however natural they may be.

I am fortunate enough to have many people in my life willing to lend me their strength in this fight. Connections are what get us through this shit, but they're not enough. I also have to have compassion enough for the survivor inside me, to forgive her when trauma rears its ugly head.

No comments:

Post a Comment