design now available here!

Sampling the yellow Charms, harmless little lemon-flavored snacks, was rumored to be the reason many vehicles broke down. The green ones, innocently flavored as lime, might as well have been rain-sticks, causing sudden storms that flooded the desert paths. And if you touched the ominous dark red ones, tasted the sugary raspberry sweetness-- well, that was the taste of death.

We'll never know if raspberry Charms were the true killers, cursing soldiers with fatal bad luck. There's no rational, scientific way to measure juju. Even so, the belief permeated the armed forces. Some veterans tell stories of commanding officers ordering the candies be disposed of, on threat of disciplinary action should any man be caught with them in his mouth. So when the candies were removed in 2007, there wasn't much outcry from the enlisted.

It can seem silly to those of us far out from the front lines, hearing about grown men and women fearing candies because of some supposed back luck. But the thing you have to understand is this is what human nature is.

Our species rules the earth. We've built towering cathedrals that reach up into the heavens. We've put ourselves on the moon, and learned how to cut each other open and slice out diseases. We wage wars and write epics about journeys across the seas. Many of us won't know death until well into adulthood, at far lower rates than those our ancestors saw. It feels at times like we're on the brink of invincibility, one miracle drug away from immortality itself.

But the humans who know death intimately may see things in a different light. It's true that the end is just one accident, illness, or chance encounter away from us all. But when those situations are as unlikely as they are to most of us, it can be easy to dismiss thoughts of them as "irrational fears" or "paranoia."

Emergency room staff, many of whom are doctors and nurses with extensive scientific education, are known to tout their own superstitions. "The q-word" is a taboo in many hospitals, as any acknowledgement of a lack of activity is bound to invite an influx of it. Some refuse to order Chinese food while on the clock, believing it will portend disaster. Saying the name of a regular patient will draw them in, and tying a knot in a patient's bedsheet will expedite their fate, speeding along their recovery or bringing about more quickly the end of their suffering.

First responders, like soldiers and E.R. staff, are notoriously superstitious creatures. We have rites, rituals, and rules, and tokens that we believe (with varying degrees of seriousness) will protect us from danger. Many of the rules in Dispatch are mirrored in other fields: don't invoke the Q-word, don't say the name of a frequent flier unless you want them to make a sudden appearance, and beware the full moon-- those nights, as well as the Fridays that land on the thirteenth of the month, will be the longest of your career. I also have it on good authority that most firefighters will be extra sure to put their turn-out gear in exactly the same place every time. "Goodbye" is an underutilized salutation for both fire and police personnel, with many preferring the more optimistic, "See you later."

|

| "Horseshoe, Dice, and Four-Leaf Clover." 2024, ink on paper. Okay, so I'm not an artist. Sue me. Anyway, that's the pen. |

Do these rituals actually do anything? Will losing my pen really cause the day to spiral into chaos, or is the added weight of its heavy tactical design merely a comfortable familiarity to which I have assigned some meaning?

One of my oldest friends was a girl named Rosie, with whom I had attended first grade. As with all long-term friendships, we would occasionally fight. But no matter how angry we got with each other, she would never let me leave the fight until she had said, "I love you," and heard me say it back. For years, I never understood why she was like this, until one day in high school when she finally told me.

One day, when Rosie was only ten or eleven, she had gotten into a big fight with her mother. Just before she stormed off, she'd called out over her shoulder, "I hate you, Mom!"

None of us had seen it coming when she died. It was a freak accident. One of those things you never see coming. And the last thing Rosie had ever said to her was, "I hate you."

Suddenly, my friend's fixation made sense. She'd been traumatized by the death of her mother, and it had been made worse by the last words she said to her.

|

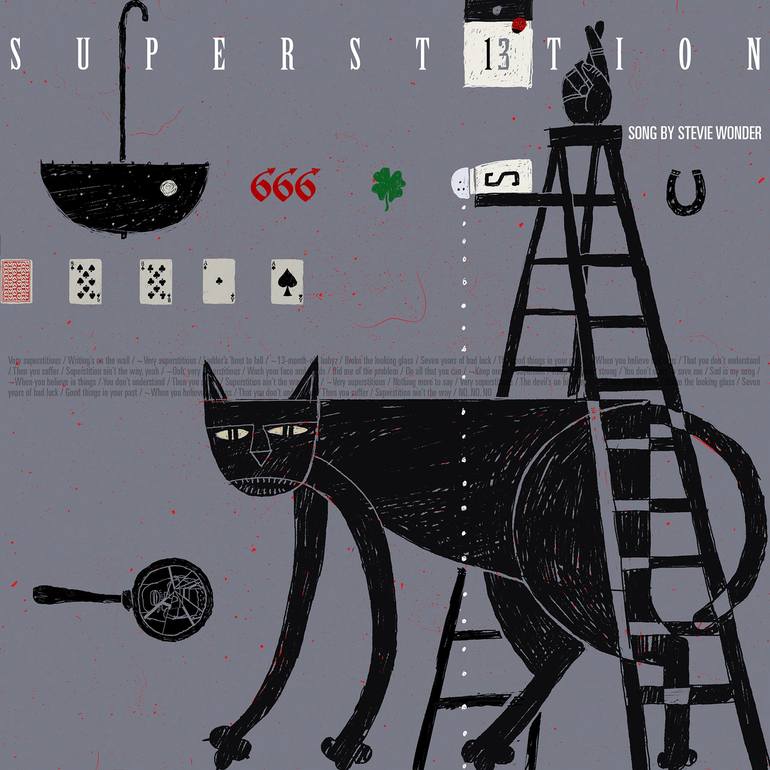

| Robert Meganck, "Superstition" |

We've all been traumatized by something terrible happening on the one day we couldn't find our coin, our lucky pen, the bracelet with our girlfriend's name on it. Made mistakes when writing on the back of yellow paper. Lost someone after a fight gone unresolved. And so we all find comfort in the things that give us a feeling of control, illusory as it may be. They allow us to feel as though there's some pattern, some meaning behind all the seemingly random ways in which life can go terribly wrong.

My house burned down on the one day I didn't have my purse; now I carry a backpack with everything I might need if I have to spend a night somewhere unexpectedly.

Rosie always ends a fight with, "I love you."

Firefighters don't say goodbye; only "See you tomorrow." Nurses never comment about it being "the Q-word," and you'll be hard pressed to find a soldier willing to carry a white lighter.

And all of us agree: never, ever eat the Charms.

No comments:

Post a Comment